Poem de Terre

I’m not a normal person

whatever that may be

there is something very very vegetable

about me,

this human skin I’m skulking in

it’s only there for show,

I’m a potato.

You only seem to hear the word ‘quintessentially’ in front of the word ‘British’, and similarly, people always seem to use the word ‘humble’ when referring to the potato. But there’s nothing humble about the potato. And I love them.

When my amazing partner decided she needed to lose 20kgs, she ate precisely 100gms of boiled potato for lunch every day for months. Potatoes are a nutritional powerhouse, you see, especially when you eat one in its whole, unprocessed form, particularly with the skin on.

Sadly often lumped in with fast foods as unhealthy, your average medium-sized potato (about 150–170 grams), boiled or baked without added fat or salt, delivers a surprisingly rich and balanced nutrient profile.

Potatoes are mostly starchy (complex) carbohydrates, which provide a slow and steady release of energy. Despite their reputation for being high carb, potatoes are naturally low in fat, with almost none, in fact, but contain only moderate amounts of protein. However, the protein they offer contains a good balance of essential amino acids.

But did you know a single medium potato can supply around 30% of the recommended daily intake of Vitamin C!? Potatoes also offer a respectable amount of several B vitamins, especially B6, which supports your brain health and energy. Small amounts of niacin, folate, thiamine, and riboflavin are also present, contributing to overall cellular function and energy production.

And potato is one of nature’s best sources of potassium - more than a banana! Other important minerals include magnesium and iron. Trace amounts of zinc, phosphorus, and manganese also contribute to the potato’s nutrient density.

Vegans should eat skin!

Don’t discard your potato skins, if you’ve gone wild with the peeler. I peeled some spuds just last night, and air fried the skins doused in smoked paprika, cumin and garlic powder. Delicious! The skin is where many of the potato’s dietary fibres and micronutrients are concentrated. Leaving the skin on increases fibre content significantly, aiding in digestion and contributing to a feeling of satiety. That fibre, combined with resistant starch that forms when cooked potatoes are cooled and then reheated, helps support a healthy gut microbiome and can aid in blood sugar control.

Of course, the nutritional profile changes dependant on how you cook them — baked, boiled, steamed, or roasted without excessive oil or salt, for example — taking a potato from a health food to a guilty pleasure.

Phew. Like I said, far from humble…

Global Timeline of the Potato

· 8000–5000 BCE: Indigenous peoples in the Andes Mountains of modern-day Peru and Bolivia begin domesticating wild potato species.

· 2500 BCE: Archaeological evidence of potato remains found in central Peru, indicating early cultivation.

· 1530s: Spanish conquistadors encounter potatoes in South America and introduce them to Europe.

· 1570s: Potatoes are cultivated in Spain and gradually spread across Europe.

· 1589: Sir Walter Raleigh is credited with planting potatoes in Ireland, where they become a staple.

· 1600s: Potatoes reach parts of Asia and Africa through European trade routes.

· 1719: First potato patch planted in North America by Irish immigrants in New Hampshire.

· 1845–1850: The Great Irish Famine occurs due to potato crop failures caused by late blight disease.

A cultivation meditation

We shouldn’t mindlessly consume anything, but the potato deserves special respect in my book, given its long and troubling history.

The potato’s evolution is rooted in the broader story of exploitation, erasure, and cultural appropriation that defined European colonisation of the Americas.

As far as I know, it began as a sacred crop of the Indigenous Andean peoples, cultivated over thousands of years in a sophisticated agricultural system. But when Spanish conquistadors arrived in South America in the 16th century, they didn’t just conquer the land, of course, they extracted knowledge, plants and people.

The potato was just one of many crops taken from the New World and shipped back to Europe as part of the Columbian Exchange, a vast and violent reshaping of the world’s ecosystems and economies. (As an aside, if you’re in London anytime soon, there’s a great exhibition at the British Library, Unearthed, which mentions the deep impacts of shipping non-native species to Europe, and it’s fascinating…)

In Europe, the potato even became a tool of state control.

Governments promoted its cultivation to feed growing urban populations and standing armies. In Ireland, for instance, the British Empire encouraged reliance on the potato because it produced high yields on small plots, perfect for a colonised, impoverished peasantry forced to export their better crops (like grain and cattle) to England. When the potato crop failed in the 1840s due to blight, over a million Irish people died in the Great Famine, while colonial policies prevented adequate relief. Here, the potato stands as both sustenance and as a symbol of systemic neglect.

Meanwhile, in Africa and Asia, European powers introduced the potato as part of their agricultural colonisation, reshaping local food systems to support imperial needs, often at the expense of indigenous knowledge and biodiversity.

When something as simple as a root vegetable can carry the weight of conquest, empire, and survival, eating it surely holds significance?

The next time you order a bag of chips, take a moment to think about its journey throughout a millennia to get to your mouth…

The Irish Famine (1845–1852)

During British rule, over 3 million Irish people depended almost entirely on the potato for nourishment due to land policies that forced them onto small, poor-quality plots. While the potato provided high calories per acre, this mono-reliance made the population extremely vulnerable. When potato blight struck, the impact was catastrophic.

Around 1 million people died from starvation and related diseases. Another 1 to 2 million were forced to emigrate, mostly to the United States, Canada, and Australia, permanently altering Ireland’s population and social fabric.

What deepens the tragedy is that Ireland continued exporting food - beef, grain, and butter, for example - throughout the famine. These exports went to Britain and its colonies, a stark example of colonial priorities outweighing human lives.

“The almighty power of England was never more sternly exercised than in the administration of Irish relief... the peasantry perished in sight of granaries they had filled.”

· John Mitchel, Irish nationalist and political journalist, 1854

Mitchel’s words reflect the bitterness felt by many: that the potato famine was not merely a natural disaster, but a political and colonial failure, even a genocide by neglect. The potato became a symbol not just of survival, but of oppression and resistance.

The Potato’s Origins in the Andes

Long before Europeans arrived, the Indigenous peoples of the Andes, especially in modern-day Peru and Bolivia, had developed a sophisticated relationship with the potato. They cultivated thousands of genetically diverse varieties, adapted to different altitudes, climates, and soil conditions. Potatoes were central not only to diet, but to medicine, trade, and spiritual life. The Inca, for example, developed agricultural terraces and freeze-drying techniques to create chuño, a preserved (dehydrated) potato that lasts for years and is still made and eaten today.

This ancestral knowledge wasn’t just agricultural; it was ecological and spiritual. Potatoes were grown in harmony with nature and used in ceremonial practices linked to the Pachamama (Earth Mother).

When the Spanish invaded the Inca Empire in the 16th century, they were less interested in the potato itself and more in gold, silver, and land. But they quickly recognised the potato’s value. Unlike wheat or barley, the potato thrived in high altitudes and poor soils. By the 1570s, Spaniards were exporting potatoes to Europe.

And in 1571, Mrs Miggins’ Fish and Chip shop opened in London. Probably.

This marked the beginning of biopiracy - the theft of biological resources and knowledge from colonised peoples. Indigenous agricultural knowledge was appropriated without credit or compensation, and the potato was absorbed into the colonial system as a commodity. Its Indigenous origins were erased in European discourse; no Inca farmers were named in European botanical records.

Ironically, while the potato propped up European empires, Andean food systems were destabilised. The Spanish introduced European crops and livestock (wheat, cattle, pigs), which displaced native agriculture. The forced labour system (encomienda) and land seizures further disrupted Indigenous farming traditions.

Over time, the potato remained in Latin America, but not always with the same centrality. It had been reframed as a European success, even as the communities that created it were impoverished and marginalised.

Today, there’s a growing movement in Latin America to reclaim native crops and Indigenous agricultural heritage. Organisations and communities in Peru and Bolivia are working to protect potato biodiversity and revive traditional knowledge. The potato is no longer just a food: it’s a symbol of cultural survival and ancestral wisdom.

Meanwhile, the UK is awash with processed potato products, and our love of a bag of chips — literally the blandest thing on earth — resolutely remains a staple meal. You can even eat it with a potato fritter and a bag of crisps, if you like.

Potatoes are a nutritional powerhouse, an instrument of deep social issues and control, a political weapon (remember, ‘Freedom Fries’ anyone?) and they’re bloody tasty, when cooked right.

My cronky maths — with a bit of help from Mintel — estimates that we Brits buy 17.5 million bags of crisps EVERY day in the UK.

Shameless Plug: I’m walking at least 62 miles throughout May in support of Dementia UK - and every penny helps them complete their vital nursing work.

You can sponsor me here.

UK fisheries suggests that an astonishing 457,000 portions of fish and chips are consumed every day across the country. Even allowing for the thousands of poor confused and disappointed tourists thinking they’re going to get a tasty meal, that’s a tonne of potatoes. And I can’t even do the maths for stand-alone ‘bags of chips’, and those sold from the likes of chicken shops, kebab houses and other takeaways!

Hogarth’s long-lost depiction of a fish and chip shop in 1730s London…probably

I’m one of those people who doesn’t pay much attention to breeds of potato, but then it seems most of the ones supermarkets provide in the UK are generic, chosen for size over flavour.

There are more than 4,000 varieties of potato (mostly native to the Andean region), but in the UK, supermarkets offer 5-10 different types, including the disconcertingly non-specific ‘baking potatoes’.

Given the rich and fascinating history of the potato, I really think we should be giving it more respect. In a UK supermarket, if you were to say “Excuse me, could you direct me to the potato aisle, please?”, the assistant would probably point you apathetically towards the crisp aisle.

In celebration of this wondrous tuber, I’ve gathered some of my favourite global potato—focused recipes, here for the first time together for your degustation.

I keep this newsletter unshackled by subscription. By all means, go ahead and subscribe, but if you’d like to throw me some gold for my efforts, you can easily do that via kofi, here. Your £3 tip buys a lot of potatoes - thank you!

RECIPES

SMASHED POTATOES, PEAS, and CORN with CHILI-GARLIC OIL

Smashed potatoes are a fantastic way to eat spuds, and this recipe only came onto my radar after I picked up Bryant Terry’s fantastic Afro-Vegan recipe book at the Wellcome Collection a few years ago, and then immediately went out and bought my own copy (and yes, I’m the sort of person who finds recipe books in the library of a science and medicine museum).

He says the main inspirations are Kenyan Irio and Latin American tostones. Irio, the most important cultural dish of the Kikuyu people of Kenya, is a seasoned puree of white potatoes, green peas, and corn, sometimes with spinach or other leafy greens.

This deconstructed version of Irio involves steaming yellow potatoes until tender, smashing them like tostones, then baking until crispy. It’s a good appetizer or side dish…

Ingredients:

4 teaspoons red pepper flakes

⅓ cup peanut oil

1 large clove garlic, minced

3 teaspoons extra-virgin

olive oil

2½ teaspoons coarse

sea salt

12 small yellow potatoes (about 2 inches in diameter

2½ cups shelled green peas (about 2½ pounds fresh peas in the pod) or frozen, see below

2% cups sweet corn kernels (about 3 ears of corn)

¼ cup packed chopped flat-leaf parsley

Freshly ground white pepper

Preparation:

Preheat the oven to 400°F. Line a large, rimmed baking sheet with parchment paper.

To make the chili oil, put the red pepper flakes in a small heatproof bowl. Warm the peanut oil in a small skillet over medium heat, then add the garlic and sauté until fragrant and starting to turn golden, about 5 minutes.

Pour the oil and garlic over the red pepper flakes and let cool, stirring a few times, for about 20 minutes.

To prepare the vegetables, put 2 teaspoons of the olive oil and ½ teaspoon of the salt in a large bowl and mix.

Put 2 inches of water in a large pot fitted with a steamer insert and bring to a boil.

Put the potatoes in the steamer, cover, and cook until fork-tender, adding more water if necessary, about 45 minutes. Remove the steamer basket from the pot and let the potatoes cool for 5 minutes.

Transfer the potatoes to the bowl with the olive oil and toss to coat. On a clean work surface, gently press each potato with the palm of your hand — or a bottle — until about ½ inch thick. With a spatula, transfer to the lined baking sheet.

Bake for 30 to 35 minutes, until browning and crispy on the edges.

After the potatoes have been baking for 15 minutes, put the remaining 1 teaspoon olive oil and 1 teaspoon salt in the same bowl and mix well. Put about 8 cups of water in a medium pot and bring to a boil over high heat.

Add the remaining 2 teaspoons salt, then add the peas.

Return to a boil, and cook uncovered until the peas are just barely tender, 2 to 4 minutes. Add the corn and cook for 30 seconds. Drain well, then transter to the bowl with the olive oil. Add the parsley and toss well.

To serve, top each potato with 3 heaping tablespoons of the pea mixture, drizzle with the chili oil, and finish with a few grinds of white pepper.

NOTE: If you’d like to use frozen peas, thaw them, then add to the boiling water along with the corn and cook until just tender, about 5 minutes.

Post-Colonial Stuffed Hasselback Potatoes with Curried Coconut Dal & Aji Verde

These slow-roasted, Andean-style Hasselback potatoes - crispy on the outside, squidgy within - are sliced deep and stuffed with curried red lentils (a nod to Indian dal, shaped by British colonial trade) and finished with a bright, spicy Peruvian aji verde sauce. It’s a celebration of resistance and reinvention.

This dish doesn’t just taste great. I think it tells a post-colonial era story: the potato, born in the Andes, carried to Ireland where it became a survival crop, later ravaged by famine under colonial rule. The lentils reflect spice routes and British imperial tastes shaped in the Subcontinent. Aji verde reasserts the South American voice at the table.

Of course, dal and aji verde don’t belong together by tradition, but with intention and balance, they can sing in harmony. Think of dal and raita - a classic combo, but with a pared-down aji verde instead.

Serve these with grilled okra or blistered tomatoes, perhaps over a bed of sautéed amaranth greens or quinoa – as a further nod to pre-colonial Andean food.

Ingredients:

For the Hasselback Potatoes:

4 large floury potatoes (e.g. Maris Piper or Russet)

2 tbsp olive oil or melted vegan butter

1 tsp sea salt

½ tsp smoked paprika or ground cumin

Fresh thyme or rosemary (optional)

For the Curried Coconut Dal Filling:

1 tbsp oil

1 small onion, finely diced

1 clove garlic, minced

1 tsp grated ginger

1 tsp mustard seeds

1 tsp ground cumin

1 tsp turmeric

½ tsp chilli flakes

100g red lentils

300ml water

100ml full-fat coconut milk

Salt to taste

Juice of ½ lime

For the Aji Verde (Spicy Green Sauce):

1 small bunch fresh coriander

1 clove garlic

1 small green chilli (e.g. serrano or jalapeño)

2 tbsp vegan mayo or soaked cashews

1 tbsp olive oil

Juice of 1 lime

Salt to taste

2–3 tbsp cold water, to blend

Preparation:

Preheat oven to 200°C (180°C fan).

Place each potato between two wooden spoons and slice thin slits across, stopping before cutting all the way through. This gives you the signature “fan” effect.

Put them into a shallow roasting dish/ tray, drizzle with olive oil or dot generously with vegan butter, and sprinkle with salt, paprika or cumin, and herbs if using.

Bake for 50–60 minutes, basting halfway through, until crisp outside and tender inside.

While the potatoes are cooking, make the dal. Heat oil in a pan. Add mustard seeds and let them pop. Add onion, garlic, and ginger, cooking until soft.

Stir in the cumin, turmeric, chilli flakes, and red lentils. Add water and bring to a boil.

Simmer gently for 15–20 minutes until the lentils are soft. Add coconut milk and simmer another 5 minutes.

Season with salt and lime juice. Keep it thick, like a stuffing.

Aji Verde

Blend all ingredients until smooth. Adjust water and salt to get a spoonable, tangy, green sauce.

Once potatoes are done, gently fan them open and spoon in the dal, letting it nestle into the cuts.

Drizzle over generous streaks of aji verde. Garnish with coriander leaves or pickled onions.

Papa a la Huancaína (Peruvian Potatoes with Aji Amarillo Sauce)

This dish is usually served as a starter or light lunch and pairs beautifully with quinoa or corn on the cob. It captures the soul of Peruvian comfort food - bold, creamy, and a little spicy. My twist is to use a baked potato (always cook a few extra!), slice it, and then air fry the slices for 10—20 mins on a lower temperature, like 160—180C.

Ingredients:

800g waxy potatoes (e.g. Yukon Gold or Charlotte), peeled and boiled whole until tender

1–2 tbsp neutral oil (sunflower or avocado)

½ small red or white onion, chopped

1 garlic clove, minced

1–2 aji amarillo peppers (fresh or paste – adjust to spice tolerance)

150g firm silken tofu (or soaked cashews for a richer version)

3 tbsp unsweetened plant milk (oat or soy)

2 tbsp nutritional yeast

1 tbsp lime juice

½ tsp turmeric (optional, for colour)

Salt and pepper, to taste

Fresh lettuce leaves, to serve

Black olives and sliced tomato, for garnish

Preparation:

Boil the whole peeled potatoes in salted water until tender but not falling apart. Let them cool until warm, then slice into thick rounds (1–1.5cm thick).

In a frying pan, sauté the chopped onion and garlic in oil until softened. If using fresh aji amarillo, de-seed and chop it, then sauté until fragrant (if using paste, you can skip this step).

In a blender, combine the sautéed mix with the tofu (or soaked cashews), plant milk, nutritional yeast, lime juice, turmeric, salt, and pepper. Blend until smooth and creamy. Adjust consistency with more milk if needed - it should pour like a thick dressing.

Taste and adjust seasoning or heat level. Chill if preferred cold, or serve warm over hot potatoes.

To serve, line a plate with lettuce leaves. Arrange the sliced potatoes on top. Generously spoon the Huancaína sauce over them. Garnish with sliced black olives and fresh tomato.

Top tips: Texture matters - letting them cool slightly helps them firm up so they hold their shape when sliced. Your potato slices should be clean and even, not crumbly or mushy.

This dish is traditionally served room temperature or slightly chilled, with the sauce either also cool or gently warmed.

Vegan Irish Potato Cakes (Pan-Fried Fadge)

These potato cakes - and who doesn’t like saying ‘fadge’? - are perfect with a pint of Guinness (yes, it’s vegan now) and can also be jazzed up with herbs like chives or parsley, or spiced up with a dash of mustard or horseradish in the mix.

Ingredients:

500g floury potatoes (e.g. Maris Piper or Rooster), peeled and boiled

50g plain flour (plus extra for dusting)

1 tbsp vegan butter (such as Flora Plant)

½ tsp sea salt

Freshly ground black pepper

2 spring onions, finely sliced (optional, for a boxty-style twist)

Oil for frying (rapeseed or sunflower work well)

Preparation:

Once boiled, mash the potatoes until completely smooth. Add the vegan butter while the mash is warm so it melts through. Let it cool slightly before stirring in the flour, salt, pepper, and spring onions if using. Mix to form a soft dough—it should be pliable but not sticky.

Lightly flour a work surface and roll the dough to about 1cm thick. Cut into rounds with a glass or biscuit cutter, or shape into triangles for a traditional Northern Irish farl shape.

Heat a non-stick frying pan over medium heat and add a little oil. Fry the potato cakes for about 3–4 minutes on each side until golden and crisp, flipping carefully.

Serve hot with a dollop of vegan butter or oat crème, or alongside grilled tomatoes and sautéed mushrooms for a full Irish-style breakfast plate.

Vegan Pommes Parmentier

Forget homemade fries — this recipe will forever elevate your home potato wrangling.

And it comes backed by a fantastic anecdote. In 18th-century France, Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, a French pharmacist and army officer, was obsessed with the potato. During the Seven Years’ War, he was captured by the Prussians and fed almost nothing but potatoes in captivity. Instead of dying (as some expected), he realised they were nutritious and safe. In fact, he stayed quite healthy.

But back in France, the potato was still deeply unpopular. It was believed to cause leprosy, and farmers refused to plant it. So Parmentier got clever.

In 1785, he had a field of potatoes planted just outside Paris. But he posted armed guards around it, making it look very valuable, as if it were reserved for the aristocracy or royal use. Soon, rumours spread. At night, with the guards conveniently “looking the other way,” local peasants started stealing the potatoes, thinking they were getting something forbidden and luxurious.

Parmentier, of course, wanted this to happen. Within a few years, potatoes were fashionable, and even Marie Antoinette wore potato flowers in her hair at court.

Ingredients

750g waxy potatoes (e.g. Charlotte or Yukon Gold), peeled and diced into 1–1.5 cm cubes

2 tbsp olive oil (plus extra if needed)

2 garlic cloves, finely chopped or crushed

1 tbsp fresh thyme leaves (or 1 tsp dried)

1 tbsp fresh rosemary, finely chopped (optional)

Sea salt, to taste

Freshly ground black pepper, to taste

2 tbsp fresh parsley, finely chopped (for garnish)

Preparation:

Peel and dice the potatoes into small, even cubes (around 1–1.5 cm). This helps them cook evenly and crisp up nicely.

Place the cubes in a pot of salted cold water. Bring to a boil and simmer for 5–6 minutes until just tender but not falling apart. Drain and let steam-dry for a few minutes.

In a large non-stick or cast iron pan, heat the olive oil over medium-high heat. Once hot, add the potatoes in a single layer (work in batches if needed). Let them cook undisturbed for 3–4 minutes to form a golden crust, then flip and repeat on all sides.

Once they’re mostly golden, add the garlic, thyme, and rosemary (if using). Cook for another 2–3 minutes, stirring gently so the garlic doesn’t burn.

Season with sea salt and pepper. Remove from heat and toss with chopped fresh parsley before serving.

To serve: These go beautifully with vegan aioli, a dollop of cashew cream, or as a base under grilled mushrooms or tofu steaks.

Simple Spanish one-pot stew

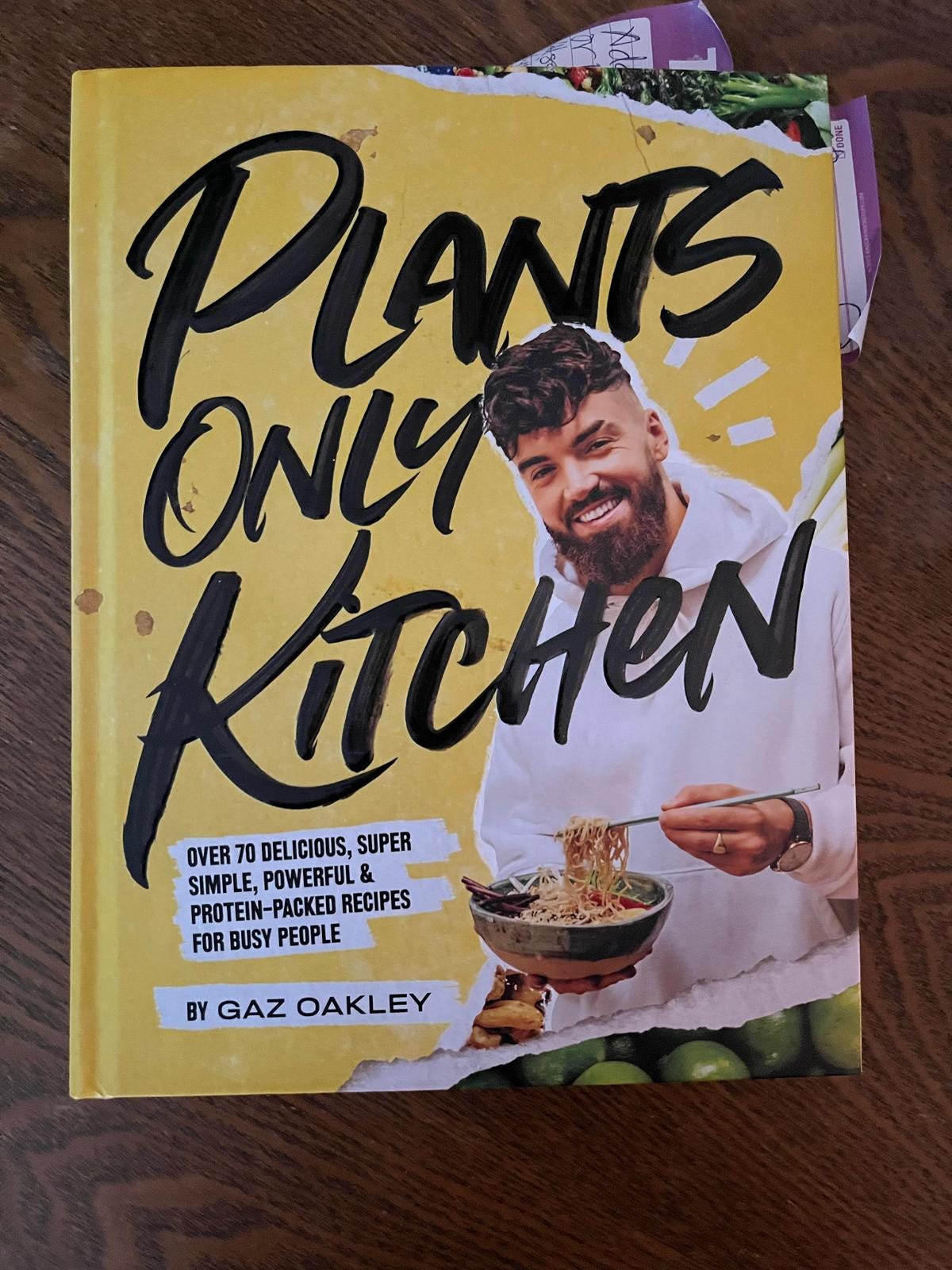

Gaz Oakley’s special stew from his book ‘Plants Only Kitchen’ has cauliflower and potatoes as a hero ingredient…

Ingredients:

Vegetable oil, for frying

2 red onions, roughly chopped

3 garlic cloves, minced

2 celery sticks, roughly chopped

1 red (bell) pepper, diced

4 tbsp smoked sweet paprika

1 tsp cayenne pepper

2 Maris Piper potatoes, cubed

½ head of cauliflower, cut into florets

1 lemon

1 bay leaf

300g (1½ cups) split red lentils, rinsed

2 x 400-g (14-oz) cans chopped tomatoes

240ml (1 cup) vegetable stock

1 tsp sea salt

1 tsp cracked black pepper

Preparation:

Place a large saucepan over a low heat and add a touch of oil (or water).

When hot, add the onions, garlic, celery, red (bell) pepper, paprika and cayenne pepper. Sauté the mixture for a couple of minutes.

Add the potatoes and cauliflower, then put the lid on. Allow everything to cook for a good 10 minutes, stirring every now and then.

When the potato has softened, cut the lemon in half, squeeze in the juice and then throw in the halves — but remove before serving. Add the bay leaf, lentils, chopped tomatoes and stock and give everything a good stir.

Season with a little salt and pepper, then pop the lid back on and let the stew simmer for 20-25 minutes, making sure you stir every couple of minutes.

Once the sauce has thickened and it smells beautiful, serve it up with some vegan sour cream and fresh chopped parsley.

Thai Massaman Curry — inspired by Poo

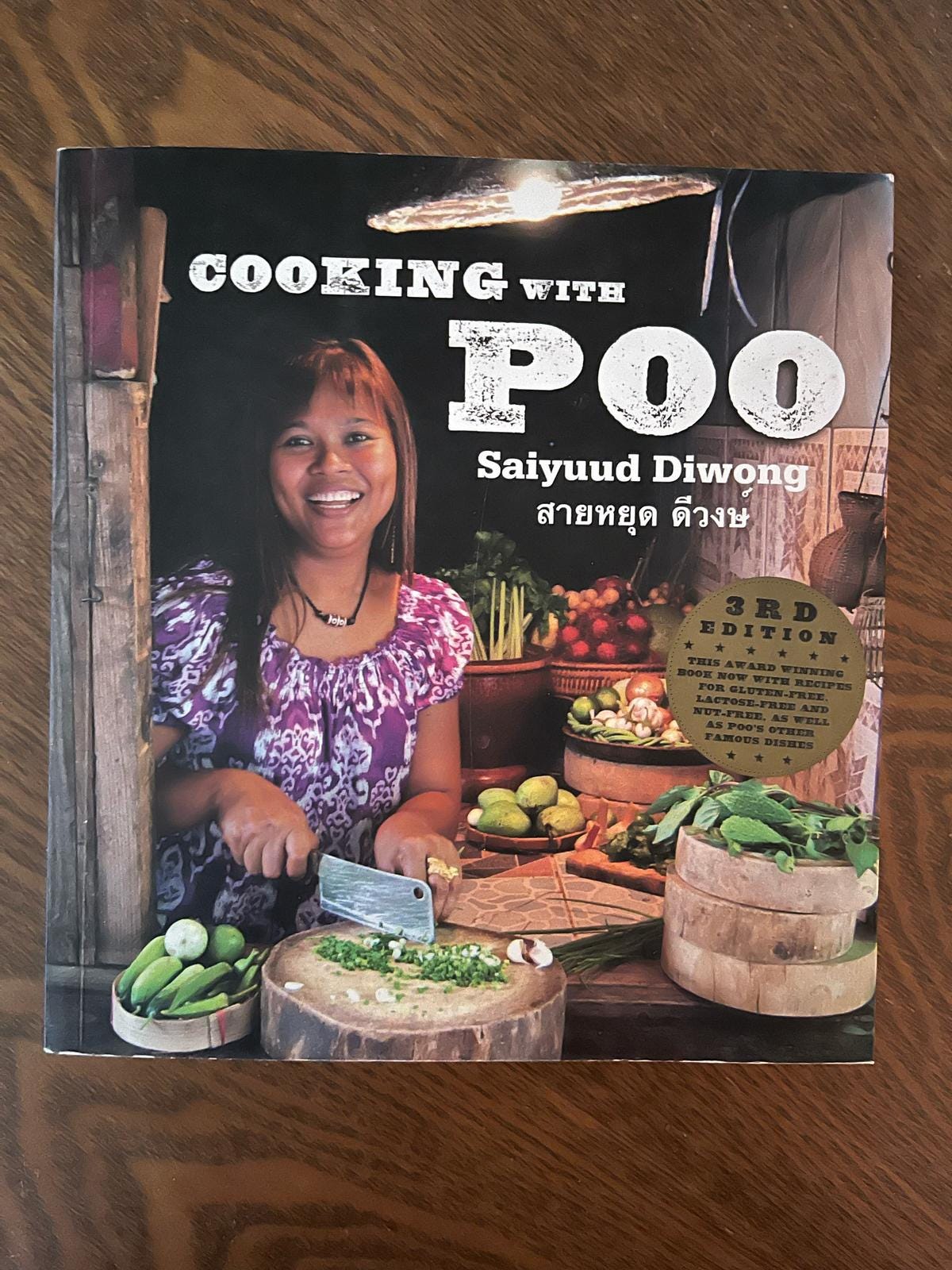

I looked forward to writing ‘inspired by poo’, if only for the intrigue the phrase may cause. But Poo (Khun Saiyuud Diwong) is an epic cook from Bangkok, who has raised herself and her community through her cookery. And I’ve got her charity recipe book, Cooking with Poo, again, mainly because the title amused me. Turns out it’s full of great recipes, and Massaman has always been a favourite of mine - it’s less spicy than green or red curries, and by using cardamom and cinnamon, it makes it more akin to some Indian curried dishes.

Ingredients:

500ml coconut milk

400g tofu, alt—meat or protein of choice, cubed

100g roasted peanuts

4 tsp sugar and a pinch of salt

¼ cup tamarind paste (found at Asian grocers)

2 bay leaves

1 cup water

2 potatoes (cut into big cubes)

2 brown onions (cut into big cubes)

4 tsp oil

MASSAMAN CURRY PASTE

10 dried red chillies (large)

2 tsp galangal (cut into small pieces)

4 tsp lemongrass (cut into small pieces)

2 tsp pepper

2 tsp garlic cloves

2 tsp red onion

2 tsp coriander seeds

1 cinnamon stick

2 tsp fennel

[Note: Massaman curry paste can be purchased at most Asian food stores, and can be used as a substitute for homemade paste.]

2 cloves

2 tsp cardamon powder

Preparation:

Dry stir-fry chillies, galangal, lemongrass, pepper, garlic, red onion, coriander seeds, cinnamon stick, fennel, cloves and cardamom until there is a change in colour (usually 5 minutes, put into a mortar and pestle and grind to a paste (or use a food processor)

Heat oil in a wok or large pan

Add paste and stir-fry for 3-4 minutes

Put in a bowl and set aside

Heat 250ml coconut milk in a saucepan until boiling

Add curry paste and tofu/ protein and cook for 5 minutes while stirring

Add peanuts, sugar, salt, tamarind, bay leaves, 250ml coconut milk, water and potatoes and simmer for 30 minutes

When the potatoes are soft add brown onion and simmer for 5-7 minutes

Serve with rice and/or roti.

Dauphinoise Potatoes (Gratin Dauphinois)

This is a side dish for royalty, in my humble opinion! A proper dauphinoise is a celebration of comfort, indulgence, and French culinary precision. Take your time with this, it’s a good thing to accompany a Sunday roast, for example…

Ingredients:

1200g floury potatoes (Maris Piper or King Edward), peeled and thinly sliced (2–3mm)

300ml vegan cream (e.g. in the UK, Oatly Creamy Oat or Elmlea Plant)

150ml unsweetened oat or soy milk

2–3 garlic cloves, finely minced

2 tbsp vegan butter (plus extra for greasing the dish)

1 tsp sea salt

Freshly ground black pepper, to taste

1 tsp Dijon mustard (optional)

A few sprigs of thyme, leaves only (or ½ tsp dried thyme)

Pinch of freshly grated nutmeg

2 tbsp nutritional yeast (optional, for cheesy umami)

Preparation:

Preheat the oven to 160°C fan (180°C conventional / 350°F).

Grease a baking dish (approx. 20x30cm) with vegan butter.

In a saucepan, combine the vegan cream and oat milk.

Add garlic, salt, black pepper, thyme, nutmeg, and mustard (if using).

Warm gently over low heat until aromatic, but do not boil.

Add nutritional yeast if desired and stir well.

Layer the sliced potatoes in the dish, overlapping slightly.

Pour over a little infused cream with each layer.

Continue layering until all potatoes and cream are used.

Press down gently to compact the layers.

Dot the surface with small pieces of vegan butter.

Cover tightly with foil and bake for 45 minutes.

Remove foil and bake for another 30–40 minutes until golden and tender.

Let rest for 10–15 minutes before serving to set.

This was bliss, Will! Thanks for the 'mash up'... Love, Lx

A wonderful work in praise of the potato with some great recipes to try . Thank you Will